On Monday of this week, the AP reported that bio-medical engineer and entrepreneur Donald Shiley and his wife, Darlene, had pledged the University of Portland its largest donation ever. It is but one example of the impact of Catholic businesspeople on the Church in America over the course of its history.

On Monday of this week, the AP reported that bio-medical engineer and entrepreneur Donald Shiley and his wife, Darlene, had pledged the University of Portland its largest donation ever. It is but one example of the impact of Catholic businesspeople on the Church in America over the course of its history.

French trappers and traders—such as the explorer Louis Joliet—might be considered the first businessmen in what would become the United States. Later, Charles Carroll was not only a well-known revolutionary; he was also among the wealthiest men of the era. Better known for his activity in public office, he also conducted business in a way common among substantial men of the time—by managing his 10,000-acre estate in Frederick County, Maryland. Philadelphia merchants Stephen Moylan and Thomas FitzSimons were also Catholic patriots. Moylan fought in Washington’s army and FitzSimons signed the Constitution as a delegate from Pennsylvania.

Philadelphian Mathew Carey’s business was publishing. Carey’s faith and business were closely integrated when his company published in 1790 the first American edition of the Douay-Rheims translation of the bible—a conspicuously Catholic endeavor in a strongly Protestant nation. New Yorker Cornelius Heeney helped to establish St. Peter Church, which would become a prominent place of worship in the New Republic. Among its parishoners was Pierre Touissant, a former slave who fashioned a successful hairdressing business.

There were Catholic businesswomen, too. Margaret Haughery was an entrepreneur who began bakery and dairy businesses in New Orleans in the antebellum period. Her business success enabled her to fund Catholic charitable causes and she cooperated especially with the Sisters of Charity. Gabriel and Felicité Girodeau hailed from New Orleans, but the pair of free blacks ran a business in Natchez, Mississippi, where they were pillars of the local Catholic Church.

During the same era, John McLoughlin headed the Hudson Bay Company and was instrumental in settling the Oregon Territory. A convert to Catholicism, he supported missionary activity by both Protestants and Catholics in the mostly unchurched northwest.

Like Charles Carroll, many Catholics in business are known to history for their roles in other activities. James Longstreet is famous as a Confederate general, but after the war he worked as an insurance and cotton broker—and converted to Catholicism.

In the nineteenth century, New York City was both the commercial capital of the nation as well as a center of Irish Catholic immigration. It is no surprise, then, that Irish Catholic businessmen were common in Gotham. William Russell Grace settled in New York in 1864. Building on success as a merchant and financier, he became the first Catholic elected mayor of New York in 1880. Construction mogul Thomas Mulry was the first president of the United States St. Vincent de Paul Society.

Catholics were also represented among the Gilded Age industrialists sometimes called “robber barons.” Thomas Fortune Ryan made his wealth building New York’s public transportation system and investing in tobacco and had a reputation for cutthroat business practices equal to any. Steel titan Andrew Carnegie’s successor was also a baptized Catholic. Charles Schwab, who was educated at St. Francis College in Loretto, Pennsylvania, built Carnegie’s company into US Steel, one of the largest firms in the world. Schwab (pictured at right) did not practice his faith regularly, though his sister became a Franciscan nun.

Catholics were also represented among the Gilded Age industrialists sometimes called “robber barons.” Thomas Fortune Ryan made his wealth building New York’s public transportation system and investing in tobacco and had a reputation for cutthroat business practices equal to any. Steel titan Andrew Carnegie’s successor was also a baptized Catholic. Charles Schwab, who was educated at St. Francis College in Loretto, Pennsylvania, built Carnegie’s company into US Steel, one of the largest firms in the world. Schwab (pictured at right) did not practice his faith regularly, though his sister became a Franciscan nun.

Although Schwab was not terribly concerned with the relationship between his faith and his business, many Catholics in commerce in the progressive and Depression periods were. Some of these became involved in an initiative intended to foster dialogue between business professionals, clergy, and labor leaders, the Catholic Conference on Industrial Problems (CCIP).

From its beginning in Milwaukee in 1923, the proceedings of the CCIP displayed a common problem: Catholic businesspeople and Catholic clergy frequently held opposing positions on economic policy issues. Historian Aaron Abell observed that employers were a minority among the Conference’s participants and this led to an anti-business bias. Interest in the CCIP declined steeply in the late 1930s.

A prime example of Catholic businessmen’s differences with other Catholics concerned the agenda of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Although most Catholics supported it, many Catholic executives did not. Ernest DuBrul, who had been a vice president of the CCIP and was an officer in a machine tool trade group, argued in the pages of Commonweal that the Agricultural Adjustment Act (1933) was “immoral.” Du Pont executive John Jakob Raskob helped to organize the anti-New Deal Liberty League.

Even among Catholic business owners, however, there were those who supported the New Deal. P.H. Callahan, president of the Louisville Varnish Company, had teamed with Msgr. John Ryan to create a profit-sharing plan at his company. Later, he defended Ryan’s endorsement of Roosevelt’s policies. Oil executive Michael O’Shaughnessy, meanwhile, criticized capitalism and advocated a cooperative industrial system that was based on the recommendations made by Pope Pius XI in his 1931 encyclical, Quadragesimo Anno.

Outside the realm of political and industrial policy, many Catholic businesspeople offered their resources at the service of the Church and society. Francis Drexel, a Philadelphia banker, provided the fortune with which his daughter, Katharine, funded numerous Catholic endeavors. Katharine inherited not only his wealth but also his belief that it should be used for the betterment of others. Another Philadelphia businessman with a famous daughter was Irish-American construction magnate Jack Kelly. His daughter Grace went from the east coast to the west and became a motion picture celebrity.

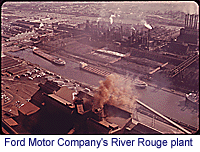

Archbishop Fulton Sheen was also a media celebrity, who counted business figures among the converts he instructed. Clare Boothe Luce, the wife of Time, Inc., president Henry Luce, embraced Catholicism in 1946. Clare Luce died in October of 1987, exactly ten days after the passing of another Sheen convert, Henry Ford II. The grandson of the Ford Motor Company founder and soon-to-be corporation president, Henry II entered the Church in 1940 in preparation for his marriage to Anne McDonnell. The controversial character of the move by someone of Ford’s standing was evinced by the piles of mail he received “telling him what a terrible thing he was doing.“

Archbishop Fulton Sheen was also a media celebrity, who counted business figures among the converts he instructed. Clare Boothe Luce, the wife of Time, Inc., president Henry Luce, embraced Catholicism in 1946. Clare Luce died in October of 1987, exactly ten days after the passing of another Sheen convert, Henry Ford II. The grandson of the Ford Motor Company founder and soon-to-be corporation president, Henry II entered the Church in 1940 in preparation for his marriage to Anne McDonnell. The controversial character of the move by someone of Ford’s standing was evinced by the piles of mail he received “telling him what a terrible thing he was doing.“

The union of Henry and Catholicism did not survive the divorce of Henry and Anne, however, and both drifted from the Church after their 1963 split. One cause of the split was Henry’s relationship with a woman he met at a Paris party hosted by Grace Kelly (a revelation published in an article that appeared in Henry Luce’s Time magazine).

Nineteen sixty-three was also the year that the country’s first Catholic president was assassinated. The foundation for John F. Kennedy’s political success lay in the financial power created by Joseph Kennedy’s business success. The Kennedy patriarch made a fortune in banking and investing.

Construction, livestock, and real estate created the wealth that the Creighton family used to establish a university in Omaha in 1878. Merchants and financiers have ever since been notable among the supporters of Catholic colleges. Besides the Shiley gift, other recent and substantial bequests include entrepreneur Robert McDonough’s to Georgetown University; Microsoft founder Bill Gates and his Catholic wife, Melinda’s, to Seattle University; Best Buy founder Richard Schulze’s to the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota; Joan Kroc’s (Minnesotan and wife of McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc) to the University of San Diego; investor William Hank and wife Joan’s to Loyola University, Chicago; the Sobratos’, a Silicon Valley real estate family, to Santa Clara University; General Electric CEO Jack Welch’s to Sacred Heart University; and Domino’s Pizza founder Thomas Monaghan’s 220-million dollar pledge to found a new university, Ave Maria in Naples, Florida.

Catholic businesspeople have enjoyed camaraderie in a number of Catholic organizations. Besides associating in common Catholic fraternal organizations such as the John Carroll Society and the Knights of Columbus, Catholics in business have joined in Catholic Business Networks in localities around the country (starting in Maryland in 1991) and a group especially for chief executives, Legatus (1987).

The spotlight has been on those who found fame or fortune (or both). But a fraction of those whose stories might be cited, these examples indicate the variety and significance of Catholic businesspeople in the history of the United States. As with every other group of Catholics, they run the gamut from saintly to roguish. Catholics in commerce deserve attention because they have been indispensable to the funding of the Church’s mission in charity and education, but also because they demonstrate the diverse ways in which Catholics have engaged American culture and economic life.

No comments:

Post a Comment